Problem 3 - Answers¶

In the problem, we will be once again building on the simulation developed in the previous problems. We will be taking advantage of our approach of simulating particles at discrete time steps to add in other kinds of forces on particles.

a) One type of force commonly considered in simulating macroparticles is drag. Modify your step function to add an additional ‘Stokes drag’ force on each particle:

Animate your simulation to see how adding drag impacts your simulation.

%matplotlib inline

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from matplotlib.animation import FuncAnimation

from scipy.spatial.distance import pdist,squareform

from IPython.display import HTML

import time

dt = 0.001

A = 1

B = 10

K = 0.1

L = 0.1

g = 10.0

def initialise(n,stdev=1.0):

poslist = []

vellist = []

n_upper = np.ceil(np.sqrt(n))

for i in range(n):

poslist.append(1/(n_upper+1)*np.array([i//n_upper+1,i%n_upper+1]))

vellist.append(np.random.normal(0.0,stdev,size=(2)))

pos = np.array(poslist)

vel = np.array(vellist)

return pos,vel

def step(n,pos,vel):

dX = np.zeros((n,n))

dY = np.zeros((n,n))

for i in range(1,n):

dX.flat[i:n*(n-i):n+1] = (pos[:n-i,0] - pos[i:,0]).flat

dY.flat[i:n*(n-i):n+1] = (pos[:n-i,1] - pos[i:,1]).flat

# calculate distances and get the matrix of force magnitudes

norms = np.sqrt(dX**2 + dY**2)

C = np.zeros((n,n))

C[norms!=0] = -1 / norms[norms!=0]**3 * np.exp(-norms[norms!=0]/K)

# multiply displacements by force magnitudes to get force vectors

dX *= C

dY *= C

# make the matrices antisymmetric

dX += -1 * np.rot90(np.fliplr(dX))

dY += -1 * np.rot90(np.fliplr(dY))

# Sum particle-particle forces to get 2D force vector

Fip = np.vstack([np.sum(dX,axis=0),np.sum(dY,axis=0)]).T

# Calculate forces due to walls at X=0,1 and Y=0,1

FW = B*(np.exp((-pos)/L)/(pos)**2 - np.exp((pos-1)/L)/(pos-1)**2)

# Calculate the drag force

FD = -g * vel

# Euler step

vel += (Fip + FW + FD) * dt

pos += vel * dt

return pos,vel

def animate(pos,vel,n,nstep,interval=20):

fig,ax = plt.subplots()

plt.close(fig)

ax.set_aspect(aspect=1.0)

ln, = ax.plot(pos[:,0],pos[:,1],'ro')

data = []

for i in range(nstep):

pos,vel = step(n,pos,vel)

data.append(pos.copy())

def init():

ax.set_xlim(0,1)

ax.set_ylim(0,1)

return ln,

def update(i):

ln.set_data(data[i][:,0],data[i][:,1])

return ln,

anim = FuncAnimation(fig,update,frames=range(nstep),init_func=init,blit=True,interval=interval)

return HTML(anim.to_jshtml())

pos,vel = initialise(100)

animate(pos,vel,n=100,nstep=1000,interval=100)

b) You’ll have noticed that a drag force causes the particles to slowly lose energy until they come to rest. This is not physical - the fluctuation-dissipation theorem says that the physical process causing drag, or ‘dissipation’ (in this case, collision with microparticles) will also cause a ‘fluctuation’. In the case of a macroparticle in a fluid, this is Brownian motion.

Add Brownian motion to your simulation. This can be represented as a force term which, at each time step, is randomly sampled from a 2D Gaussian distribution. Look up the Langevin equation for more details on this.

Make an animation and observe the effects.

T = 100.0

def step(n,pos,vel):

dX = np.zeros((n,n))

dY = np.zeros((n,n))

for i in range(1,n):

dX.flat[i:n*(n-i):n+1] = (pos[:n-i,0] - pos[i:,0]).flat

dY.flat[i:n*(n-i):n+1] = (pos[:n-i,1] - pos[i:,1]).flat

# calculate distances and get the matrix of force magnitudes

norms = np.sqrt(dX**2 + dY**2)

C = np.zeros((n,n))

C[norms!=0] = -1 / norms[norms!=0]**3 * np.exp(-norms[norms!=0]/K)

# multiply displacements by force magnitudes to get force vectors

dX *= C

dY *= C

# make the matrices antisymmetric

dX += -1 * np.rot90(np.fliplr(dX))

dY += -1 * np.rot90(np.fliplr(dY))

# Sum particle-particle forces to get 2D force vector

Fip = np.vstack([np.sum(dX,axis=0),np.sum(dY,axis=0)]).T

# Calculate forces due to walls at X=0,1 and Y=0,1

FW = B*(np.exp((-pos)/L)/(pos)**2 - np.exp((pos-1)/L)/(pos-1)**2)

# Calculate the drag force

FD = -g * vel

# Apply Brownian 'kick'

FB = np.random.normal(0.0,T,size=(n,2))

# Euler step

vel += (Fip + FW + FD + FB) * dt

pos += vel * dt

return pos,vel

pos,vel = initialise(100)

animate(pos,vel,n=100,nstep=1000,interval=100)

c) Changing the standard deviation of the Gaussian Brownian noise, you are effectively modifying the ‘temperature’ of the particle system. Repeat your animation with different ‘temperatures’ and note the effect.

T = 10.0

pos,vel = initialise(100)

animate(pos,vel,n=100,nstep=1000,interval=100)

T = 30.0

pos,vel = initialise(100)

animate(pos,vel,n=100,nstep=1000,interval=100)

T = 300.0

pos,vel = initialise(100)

animate(pos,vel,n=100,nstep=1000,interval=100)

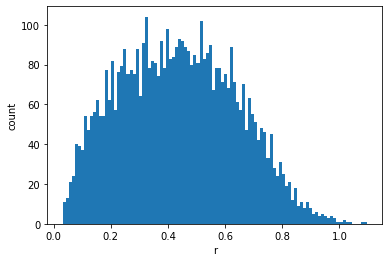

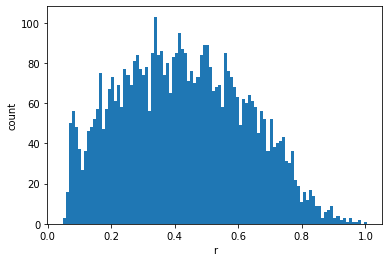

d) Clearly, the particle system is more ‘disordered’ at higher temperatures. A good way of visualising the order of a particle system is to plot its correlation function. Make and compare plots of the correlation function for different temperatures.

pos,vel = initialise(100)

T = 10.0

for i in range(1000):

pos,vel = step(100,pos,vel)

plt.hist(pdist(pos),bins=100)

plt.xlabel('r')

plt.ylabel('count')

Text(0, 0.5, 'count')

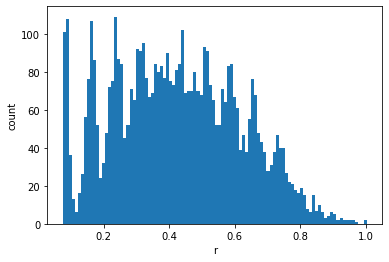

pos,vel = initialise(100)

T = 30.0

for i in range(1000):

pos,vel = step(100,pos,vel)

plt.hist(pdist(pos),bins=100)

plt.xlabel('r')

plt.ylabel('count')

Text(0, 0.5, 'count')

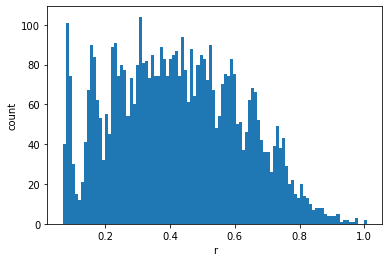

pos,vel = initialise(100)

T = 100.0

for i in range(1000):

pos,vel = step(100,pos,vel)

plt.hist(pdist(pos),bins=100)

plt.xlabel('r')

plt.ylabel('count')

Text(0, 0.5, 'count')

pos,vel = initialise(100)

T = 300.0

for i in range(1000):

pos,vel = step(100,pos,vel)

plt.hist(pdist(pos),bins=100)

plt.xlabel('r')

plt.ylabel('count')

Text(0, 0.5, 'count')